SHAFESTBURY Boys’ Club, Birkenhead’s leading youth club, played a crucial role in the Great War of 1914-18.

After the war came peace and remembrance: Shaftesbury commemorated its lost heroes in a remarkable ‘Golden Book’.

Wirral writer Mike Simpson turns the pages of history in this meticulously-researched and moving article for the Globe.

Mark Twain said of writers: "The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter — it's the difference between the lightning-bug and the lightning."

Mike Simpson always found the lightning.

ALL the lads would remember that golden summer of 1909, when they escaped Birkenhead’s ghettoes of poverty and deprivation for a week under canvas at Penmaenmawr, North Wales.

Seven carefree days when they ran and leaped and hollered, swam and played cricket from dawn to dusk before supper round a roaring campfire when they devoured heroic quantities of simple, wholesome food.

Simple food, simple pleasures; a timeless idyll under big skies.

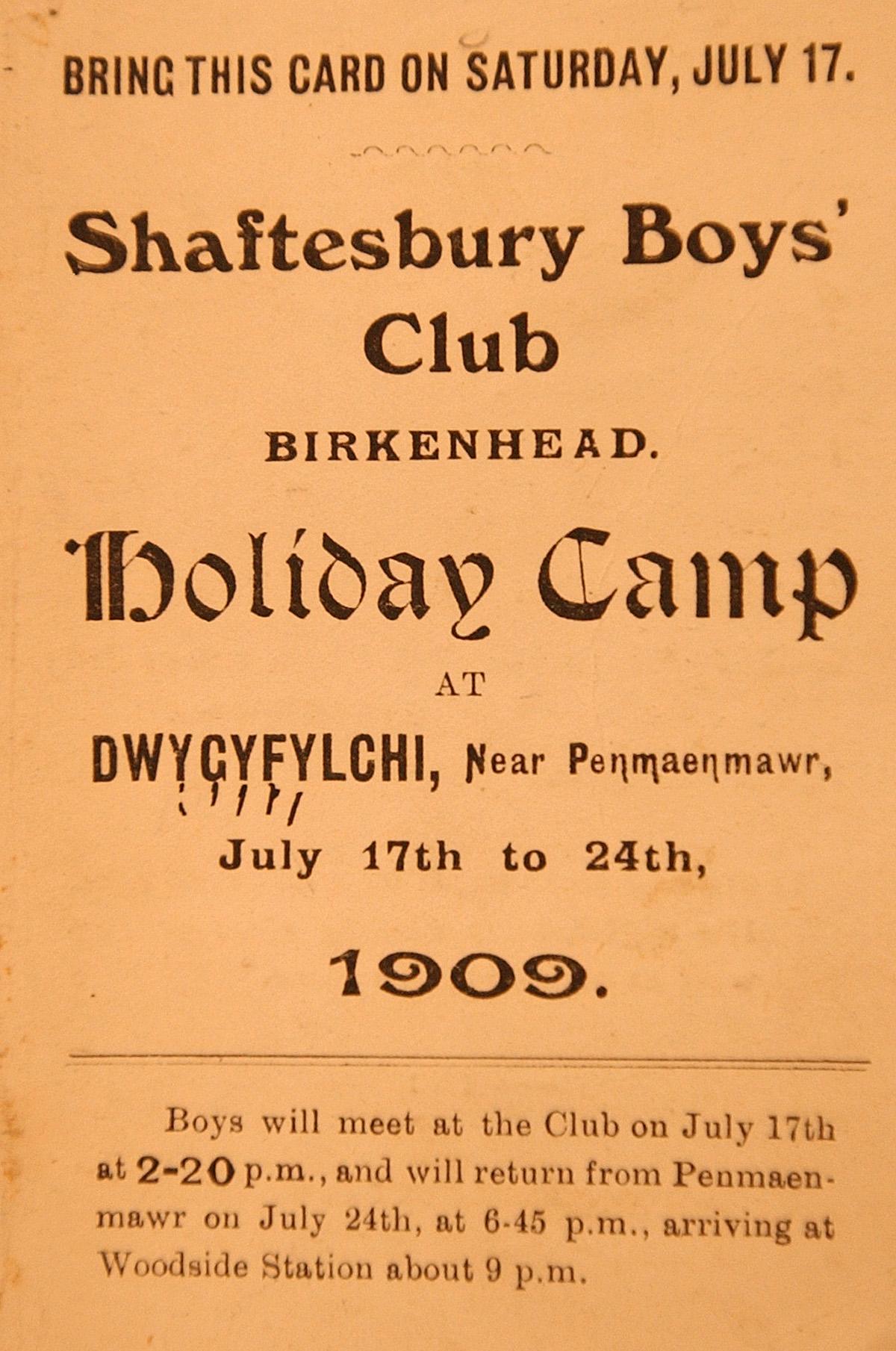

Aged between eight and 19, the 100 or so boys had grumbled as they handed over their weekly pennies towards the cost of the trip, but once paid up, each had received their official printed Camp Card - a combined pass-out and programme of events - a little bigger than a modern credit card.

Once you had that, you were on your way and nothing on this earth would stop you.

They were a reminder of happier days that they carried into adulthood.

Within five years, many would gaze wistfully at their precious mementoes during lulls in fighting on hellish battlefields around the world.

Shaftesbury remembered their absent friends throughout the war and commemorated the dead when peace, and the battered survivors, returned.

The dead were listed in a remarkable ‘Laurel Roll’ known as the ‘Golden Book’.

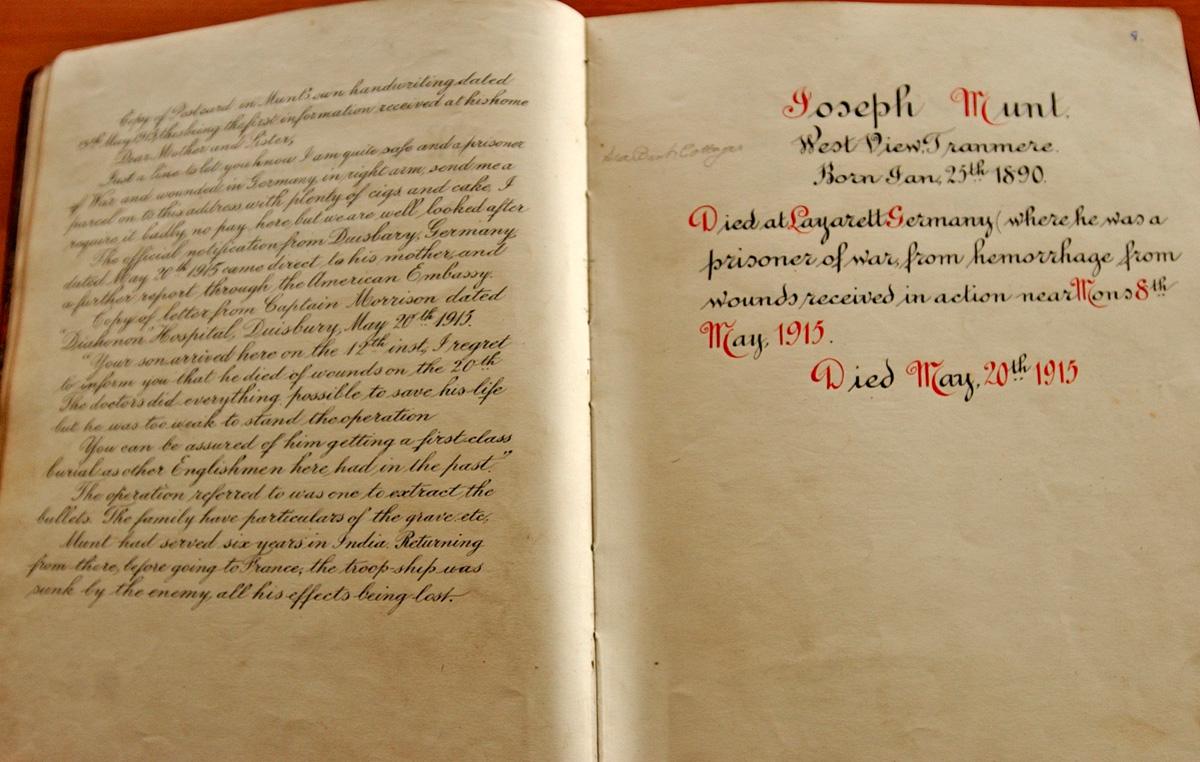

Between hand-tooled leather covers, illuminated pages record 73 names, addresses and dates of birth, regiments and the fateful actions in which they lost their lives and where the dead were buried; all in a beautiful cursive script.

It was a professsionally-produced testament to lost youth, conceived with later generations in mind, which 100 years on provides a fascinating glimpse back in time.

For alongside the sparse facts of a soldier or sailor’s death are edited excerpts from letters home; praise from commanding officers writing to inform parents and wives of their loved one’s death, and fuller descriptions of that final conflict with the enemy.

But in 1909, in that tense decade before the inevitable war with Germany, few may have imagined the scale of the slaughter to come, but preparations were quietly underway - and even the youngest were allotted a role.

With hindsight, that year’s camp carried an eerie presentiment of the horror to come; when the boys of summer would embark on a grimmer trip from which many would not return.

Shaftesbury’s camp followed unashamedly militaristic lines. Buglers sounded ‘Reveille’ at 6.30am, followed by breakfast and drill.

Adult helpers were ‘officers’, boys ‘other ranks’, from which NCOs were promoted for good, soldierly behaviour.

Prizes were awarded for ‘Best-Kept Tent’, inspections were frequent and anyone breaking one of the many campsite rules found themselves on a charge.

Self-reliance, loyalty to comrades and obedience were vigorously encouraged; the boys paraded before they played. ‘Last Post’ was always sounded at 10pm.

After war was declared in August 1914, Shaftesbury boys drilled with wooden dummy rifles and were instructed in the black arts of trench warfare.

And the club also assumed a vital community role. Members delivered coal and relief parcels to servicemen’s families and at Easter, flowers to the bereaved.

A ‘Tipperary Club’ was formed at Shaftesbury’s Thomas Street clubhouse and a room kept open all day from where letters were sent to those on active service; anxious families scanned newspapers’ ‘Missing’ and ‘Killed’ lists.

Club leader and founder WA Norrish’s corps of ‘Pioneer’ lads tirelessly ran errands and were effectively the eyes and ears of the organisation.

Through their efforts, Norrish each year prepared a printed booklet: ‘Comrades in Arms’ (now in the club’s archives at Wirral Museum, Birkenhead Town Hall), which gave details of the estimated 620 club members in uniform.

Norrish’s own ‘Comrades’, with latest postings and casualties, formed the basis for the post-war ‘Golden Book’.

Norrish was said to have annotated his copy with tears of pride and pity.

His boys were scattered far and wide ,and each entry brought a face to mind.

Many were killed yet their deeds live on in the ‘Golden Book’.

Pathos is a constant thread that runs through individual stories.

Nineteen-year-old Edward Cordon, of Lord Street, was killed by a shell splinter to the heart in France on November 24, 1917.

The South Wales Borderer’s Company Sergeant-Major wrote to the boy’s mother: “A piece of shell hit your son in the heart and he was killed instantly.

“I am glad to say he did not die in any pain and his death was instantaneous.”

The ‘good little soldier’, however, lingered long enough to whisper to comrades as he lay dying in the mud: “Tell my mother I am done.”

Twenty-one-year-old Harry Ridgway died in the Third Battle of Ypres, or Passchendaele, on June 7, 1917, while serving with the 7th East Lancashire Regiment. It was the most notorious land campaign of the war.

Ridgway’s Commanding Officer wrote home: “He led his company to the attack of two German lines in the early morning.

“Before reaching the first he was hit by a piece of shrapnel. His officers and men begged him to go back to the dressing station but he refused.

“He knew the men looked to him and at all costs he was going to take his company to the final objective.

“He was again entreated to to return to the first-aid post.

“He absolutely refused and at the appointed time led his men as though absolutely fit and stormed the second line...The whole attack was brilliant.

“No man had a more glorious death.

"His bravery will be remembered in the regiment and the greatness of his doings partly console me for the loss of a friend, as they will, I hope, soften the loss to you of a son.”

George Houghton was killed on June 19, 1917, a month before his 23rd birthday.

The 1st King’s Own Yorkshire Regiment soldier had written to friends at St Thomas Street shortly before his death.

Shaftesbury days were a memory he, like so many others, drew on and his final letter is painfully ironic.

It reads: “I have just come out of the trenches for a few days’ rest. It is hard work, but we do it for the good cause and the old motto still confronts me: ‘keep on playing the game’.

“Best wishes and kind regards to all officers of the club and I wish the opening of the next session is crowded with all the boys who are at present on active service.

“By gosh, it would be some night! May the war have a speedy termination and a speedy journey to Blighty.”

The Golden Book’s parade of the fallen reveals some fine characters, uncompromising Birkonians.

Tommy Byrne, of the 1st Cheshires (killed in northern France, September 1918) was 21. Rum was routinely issued to stiffen the resolve of men going ‘over the top’ in an attack.

But Byrne had signed the Temperance Pledge and was having none of it.

His lieutenant ordered Byrne to sup.

Byrne refused and was hauled before his company captain, who backed Byrne’s unusually sober appraisal of the realities of war.

These were tough lads from the warren of mean back streets and alleys around Thomas Street.

They had always lived by their wits and harboured few illusions about the nature of man, an attitude they found useful in the trenches or on the High Seas.

William Williams, 21, of Abbott Street, was on HMS Tipperary, one of six destroyers sunk by the mighty German guns at Jutland.

Clubmate John Quin, a 17-year-old from Leicester Street, on board the battlecruiser HMS Invincible, was lost at sea as Admiral Sir David Beatty’s fleet fought an inconclusive battle which still arouses controversy and fierce debate.

Where battle raged, on land or sea, Shaftesbury lads were in the thick of it.

Peter McNulty, of Oliver Street, was a 22-year-old who joined an elite cavalry regiment, the 13th Hussars and died a truly heroic death, galloping sword down, against the machineguns of the Turkish position at Lajj, in what is now Iraq.

Twenty-nine fellow Hussars were cut down by 20th century armaments deployed against 19th century tactics; a sadly frequent feature of the Great War.

A dispatch dated July 10, 1917, said: “A remarkable feature of the day’s work was a brilliant charge made mounted by the Hussars straight into the Turkish trenches.”

A mad dash in the desert; Death or Glory.

How poor Harry Kennedy, McNulty’s close neighbour and pal from Oliver Street, reacted to army life can only be imagined.

He died during a desperate final attempt to relieve the Turkish siege of Maj-General Charles Townsend’s beleaguered 10,000 troops garrisoned at Kut, in Iraq.

The failure of that action sealed the fate of Townsend’s force, which surrendered unconditionally on April 29, 1916. Four thousand died in captivity.

But how Harry actually got to Kut deserves a book in itself.

At the outbreak of war he was touring Germany with a company of travelling actor-comedians but escaped into France and joined the Cheshires.

An East Lancashire Regiment soldier searching for a dressing station in the aftermath of Kut found Kennedy’s lifeless body among the 2,000 allied soldiers who died in the frontal assault of April 5; comedy had turned to tragedy for brave Harry in the Persian Gulf.

And finally Edwin Alfred Roberts, of Hampton Street, killed in Flanders on October 22, 1917.

Comrades from the 16th Cheshires fought fiercely and courageously but later that night a stretcher-party searching no-man’s land for wounded - whose piteous cries could be heard in the trenches - found Roberts, beyond help.

A brief entry in the ‘Golden Book’ records: “Among the treasures carried in his uniform were his Shaftesbury Club camp card for 1909, which like other members he had always with him.”

That perfect summer; that precious card.

A memory of paradise he carried with him into the jaws of Hell.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel